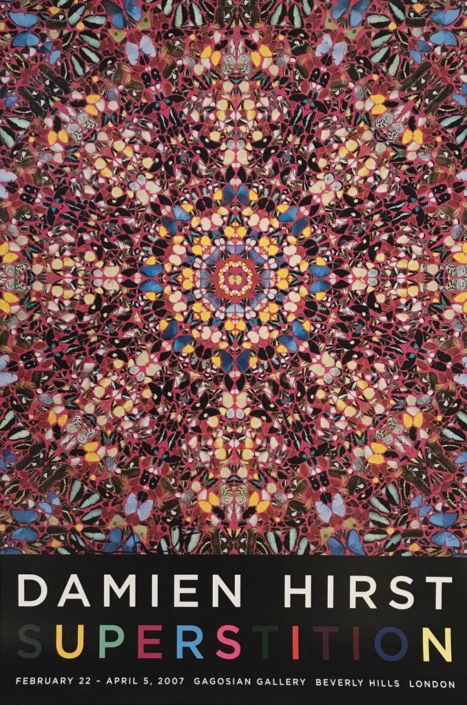

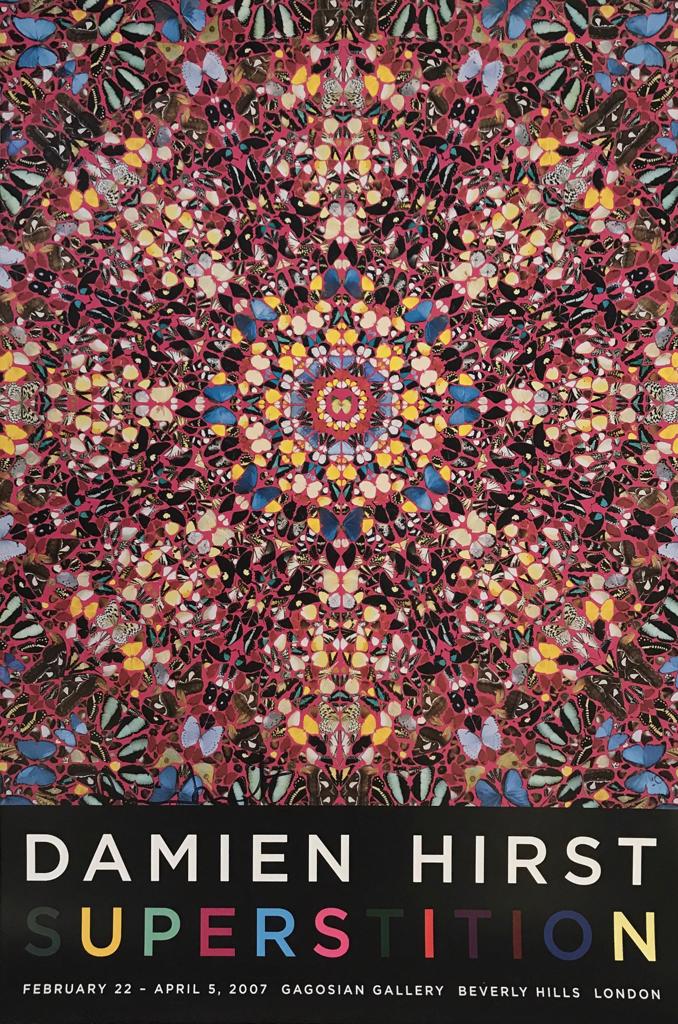

BRITISH, b. 1965

One of the late twentieth century’s greatest provocateurs and a polarizing figure in recent art history, Damien Hirst was the art superstar of the 1990s. As a young and virtually unknown artist, Hirst climbed far and fast, thanks to Charles Saatchi, an advertising tycoon who saw promise in Hirst’s rotting animal corpses, and gave him a virtually unlimited budget to continue. His shark suspended in a tank of formaldehyde, entitled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, wowed and repulsed audiences in 1991. In 1995 (the same year that he won the coveted Turner Prize) Hirst’s installation of a rotting bull and cow was banned from New York by public health officials who feared “vomiting among the visitors.” Hirst, the Sid Vicious of the art world (the Sex Pistols were his favorite band), is the logical outcome of a process of ultra-commodification and celebrity that began with Andy Warhol.