Black Paint on White Canvas

While Basquiat was a graffiti artist early in life, tagging the grubby streets of late 70s Manhattan with cryptic poems, he preferred not to be introduced that way. It was yet another symptom of being a black artist in a white artist’s world.

In the biopic Basquiat, wealthy white art collectors descend into an underground studio to watch the young, black painter at work. Basquiat hunches over his canvases, hair wild and face paint–splattered.

The onlookers are rapt with the spectacle, almost like colonizers watching a “noble savage” perform miracles. The scene resembles a zoo exhibit just enough to make one cringe.

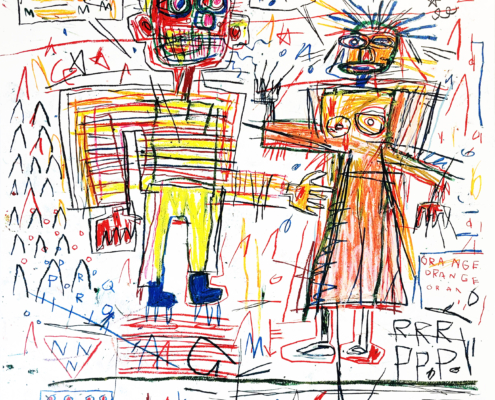

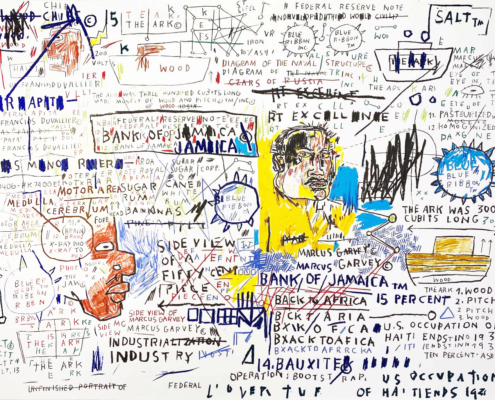

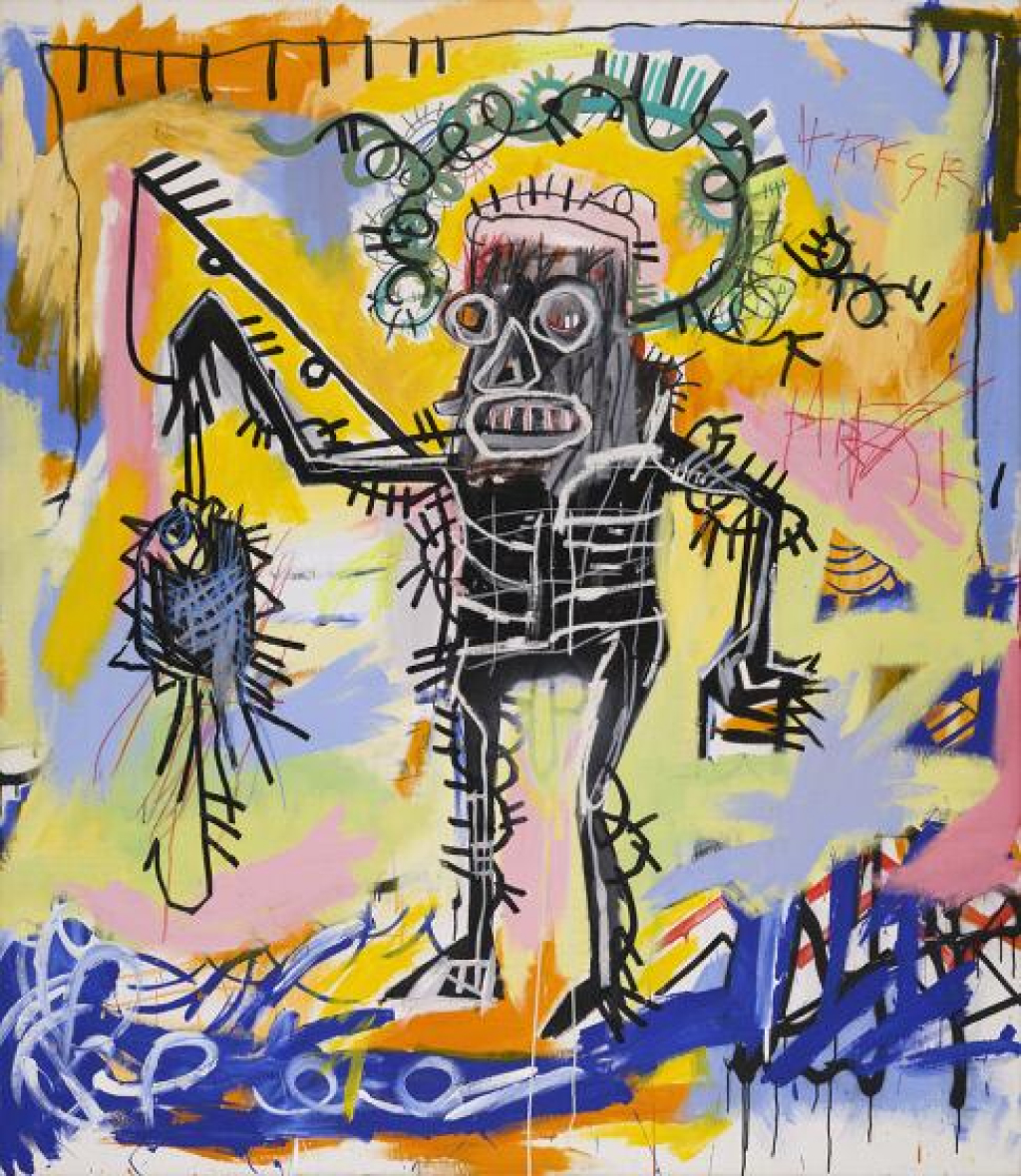

Untitled, 1981. Oil stick, acrylic, and spray enamel on canvas. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Photo by: Herry Lawford / CC BY 2.0 / Source: Flickr

How The World Saw Basquiat’s Paintings

In reality, art critics like to write that he was painting in a “basement.” Basquiat pointed out in an interview that they would simply call him an Artist-In-Residence if he were white. So too, they might have called him a street art poet instead of a graffiti artist. The list goes on.

That characterization seemed natural to the art world of the 70s, maybe for no better reason than it echoed centuries of deeply-ingrained racism. Plus there were the capitalistic benefits of creating hype around a ghetto boy endowed with visionary talent.

However, Basquiat wasn’t the uncultured “voice of the gutter” the media portrayed him to be. He received a private education and spoke three languages fluently. His knowledge of art history and academics at large was deep. Often his studio was littered with open volumes around his half-finished works.

In any case, the art world was on the mark in one respect–the man was fascinating. This article takes a deeper look at the stories surrounding Basquiat’s graffiti, painting, and other artworks.

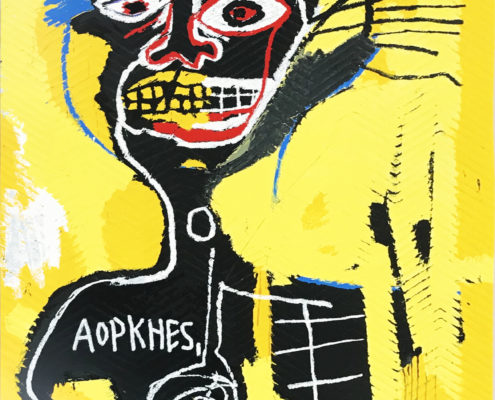

Self-Portrait (Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1986) 180×260,5 cm

Photo by: Jorge Franganillo / CC BY 2.0 / Source: Flickr

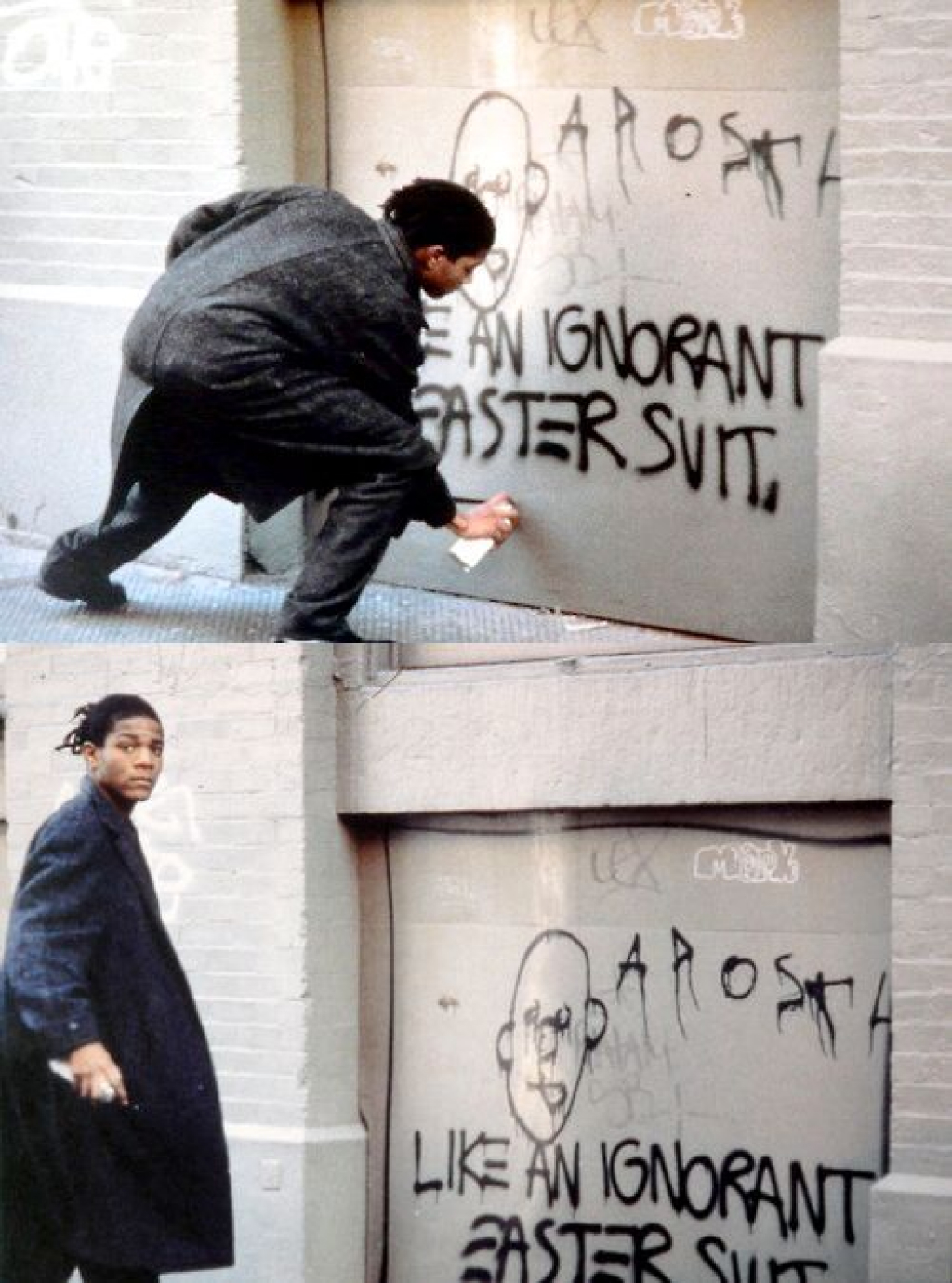

Facing Racism and Defacing Buildings

Basquiat’s graffiti was often cryptic and poetic. Watch the video below of a young Basquiat tagging the city under the name SAMO, the graffiti duo which helped bring recognition to the young artist.

Basquiat and Diaz created the moniker “SAMO” during a stoned conversation, calling the weed they smoked “the same old crap.” They eventually shortened the phrase to “Same Old” and eventually “SAMO”.

In interviews, art critics often tried to attribute lofty meanings to a particular figure or symbol. Basquiat often replied by saying things like, “No, it’s just a belt buckle” or “I just felt like painting a skull.”

Basquiat Graffiti, “Like An Ignorant Easter Suit”.

Photo by: Yukari N / CC BY 2.0 / Source: Flickr

Interpreting Basquiat’s Graffiti

So it might be best to take a simple approach to interpreting his mysterious texts. Maybe he wrote “Braille teeth” as a socio-political comment on the blind, carnivorous world. Maybe he just wrote it because he hadn’t brushed all day and his teeth felt a little bumpy on his tongue.

One reason why his street art texts tend to be wildly cryptic is that he was often stoned when writing them. The mind turns into an untamed animal that Basquiat had no desire to saddle for the sake of his readers.

In this way, he reflects the self-assured mind of an artistic genius. His expression was pure, untainted by the desire to please or be understood. And all the while his ambition craved recognition.

Basquiat Graffiti — The Whole Livery Line

Basquiat’s most famous graffiti text goes like this:

“The Whole Livery Line

Bow Like This With

The Big Money All

Crushed Into These Feet”

Without a doubt, this text has a pointed meaning behind it. The story goes that Basquiat was in front of a fine art exhibition, still young and undiscovered, and very much the outsider looking in.

The biopic Basquiat interprets the text as an expression of frustration against the racial forces that made his rise to the top especially difficult. Though he came from the middle class, his life in Manhattan was certainly that of the starved artist.

Anthony Clarke (detail) 1985 by Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Photo by: .marc carpentier / CC BY 2.0 / Source: Flickr

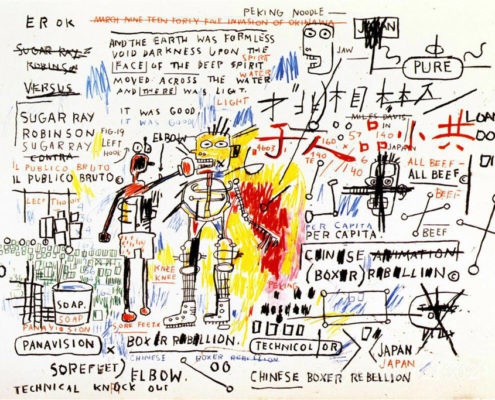

Basquiat Painting — Gold Griot, 1984

‘I’ve never been to Africa. I’m an artist who has been influenced by his New York environment. But I have a cultural memory. I don’t need to look for it; it exists. It’s over there, in Africa. That doesn’t mean I have to go live there. Our cultural memory follows us everywhere, wherever you live.’

– Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1981

A griot was a member of a class of traveling poets, musicians, and storytellers who maintain a tradition of oral history in parts of West Africa. Without a doubt, Basquiat saw himself as a griot of Manhattan.

The Basquiat painting below, completed on a series of wooden slats, represents a strong dose of his graffiti background in his mainstream pieces.

Like Picasso, the young artist believed that “people’s magic and strength rubbed off on the things they wrought”. In this case, the Gold Griot represents alchemy spread over wood and paint.

It tells the story of Basquiat’s cultural memory of his ancestral heritage, transplanted into a post-slavery world. Most likely, it is the image of an Ejagham Nnimm woman from Cambodia or Nigeria.

The Ejagham people disproved the myth that African tribes did not have a written history, as they developed a system of ideographic writing. Basquiat’s knowledge of this came from his extensive reading, and he was certain to have loved this fact enough to create an alchemical talisman of it.

Gold Griot (detail), 1984

Photo by: .marc carpentier / CC BY 2.0 / Source: Flickr

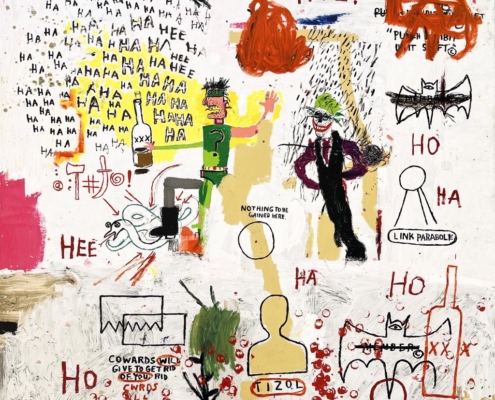

Basquiat Screenprints

Hamilton Selway provides high-quality screenprints of important Basquiat paintings. Currently we offer 50 Cent Piece, Phooey, and Jawbone of an Ass. At the time of this writing, all our editions are signed and stamped by the Basquiat estate.

Please click the links above to view the artworks and inquire about these pieces. Keep scrolling to discover more of the visionary and legendary paintings by Basquiat.

What Does Basquiat Mean?

The literal, etymological meaning of Basquiat is from French. It describes someone from the Basque Country, a region split between France and Spain.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s connection to France is rooted in his Haitian heritage, specifically through his father. Gérard Basquiat was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Haiti was a French colony known as Saint-Domingue until its independence in 1804, and its culture, language, and social systems remained deeply influenced by France long after.

It’s likely that his ancestors were enslaved Africans brought to Haiti by the French. His last name suggests there may have also been a French colonist in his lineage.

French colonists often intermarried or had children with African and mixed-race women, creating a population of Afro-French mixed descent, often referred to historically as “gens de couleur libres”.

As a result, Basquiat grew up speaking fluent French, alongside Spanish and English, making him trilingual from a young age.

His first name is the combination of the French equivalents of John and Michael, two biblical names. Jean means “God is gracious”, and Michel means “Who is like God?”.

The Meaning Behind Basquiat’s Symbols

One of the most compelling aspects of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work is his use of symbols. They are raw, recurring, and often enigmatic.

It has been said that Basquiat got his hands on a copy of Dreyfuss’ The Symbol Sourcebook, essentially the dictionary of symbols. It includes graphic symbols from folklore, hobos, and everywhere in between.

One can imagine how these would have captured the artist’s imagination when he was a graffiti artist. Indeed, many of the most common symbols in Basquiat’s oeuvre have their roots in spray paint.

These symbols are not merely visual decorations. They are charged with cultural memory, personal trauma, and pointed critique. Interpreting Basquiat’s symbols offers a key to unlocking Basquiat meaning in a deeper, more nuanced way.

Let’s take a closer look at the meaning behind his most common symbols.

The Crown

Perhaps his most iconic symbol, the three-pointed crown appears in numerous works.

It is often placed above the heads of Black athletes, jazz musicians, or anonymous figures. The crown asserts dignity and dominance in a world that tried to deny both.

It is a statement of sovereignty—Basquiat’s way of canonizing his subjects in the absence of institutional recognition.

The crown is not pristine. It’s often jagged, uneven, childlike. That roughness gives it power.

It’s not royalty bestowed—it’s royalty claimed.

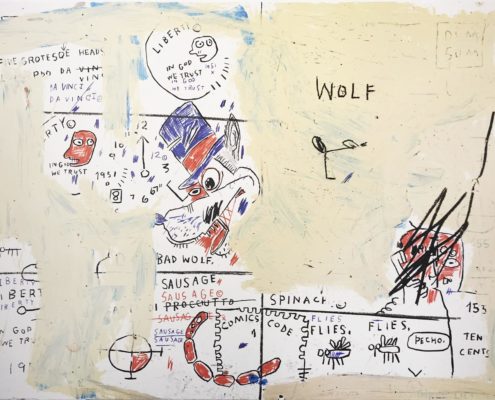

Skulls and Heads

Basquiat painted many skulls, sometimes anatomically correct, other times stylized or exaggerated. These images reflect:

- His childhood obsession with Gray’s Anatomy (a book he studied after a car accident).

- A fascination with mortality, human vulnerability, and the physical remnants of systemic violence (especially colonialism and slavery). A skull is stripped to its core.

- It may also be an artistic nod to Haitian vodou spiritual figures like Baron Samedi, as well as African masks and Dia de los Muertos imagery.

Traditionally in art history, skulls are meant to invoke memento mori and serve as a reminder of death. Basquiat’s work seems to use the symbol with more versatility.

Skulls in pieces like Red Skull (1982) and In This Case (1983) seem to channel Black identity and resistance. They challenge how Black bodies are viewed, dissected, and remembered.

In Untitled (Skull) (1982), the skull becomes a haunting self-portrait and a visual expression of anxiety, legacy, and the complex burden of visibility as a Black artist.

Teeth and Gums

Frequently exaggerated, Basquiat’s use of teeth plays with themes of consumption, aggression, and survival.

Bared teeth may symbolize raw emotion, fight-or-flight instinct, or even hunger—literal or metaphorical.

In some paintings, mouths overflow with text, showing how language itself becomes violent when consumed or misused.

Words and Repetition

His canvases are littered with single words, repeated phrases, or lists. Check out this curated list of them. Taken altogether, they become very interesting to examine:

Anatomy & Body |

Race & Identity |

Violence & Mortality |

Capitalism & Money |

Authority & Control |

| Brain | Negro | Death | Death | Sugar Cane |

| Spine | King | Suicide | Profit | Police |

| Skull | Crown | Burnt | Pawn | Judge |

| Gums | Hero | Asbestos | Dollar | Jail |

| Teeth | Royalty | Lead | SAMO© | Prison |

| Spleen | Slave | Radiation | Copyright © | Property of |

| Liver | Black | Homicide | Money | Inmate |

| Jawbone | Famous Negro Athletes | Bang | Cash | Law |

| Eye | DIZZY (Gillespie) | Shot | Pay | Sentence |

| Foot | CHARLIE PARKER | Die | Sucker | Execution |

| Heart | MOSES | POW | ||

| Pelvis | X-Ray | |||

| Tongue | ||||

| Bone |

Medicine & Science |

Pop Culture & Icons |

Religion & Myth |

Miscellaneous / Text Fragments |

| Arsenic | Hollywood Africans | Holy Ghost | SAMO© |

| Xylocaine | Joe Louis | Halo | MILK |

| Thorazine | Miles Davis | Saint | RINSO |

| Vanadium | Edison | Christ | CRUX |

| Sickle Cell | Michelangelo | Angel | PHOOEY |

| Ibuprofen | Leonardo | Devil | THE WHOLE LIVERY LINE |

| Radiation | Baseball | Exodus | IRONY OF NEGRO POLICEMAN |

| Opium | Boxer | Moses | PER CAPITA |

| Test | Jazz | VOODOO | THIS IS A PAINTING |

| Formula | Elvis | Griot | LIKE AN IGNORANT EASTER SUIT |

| TV |

These words are often written in block letters, crossed out, or partially erased. When asked about why he crossed out various words. He said, in his charmingly meek way, “So you pay more attention to it.”

Boxes and Arrows

Arrows in Basquiat’s work often serve to direct attention, frame subjects, or emphasize words. Sometimes they point toward power. Other times, they signal confusion or draw the eye toward something intentionally unsettling.

Boxes or grids (often drawn around text or figures) function as:

- Cages for thoughts

- Frames for memory

- Commentary on institutional control or categorization (e.g., hospital charts, police files)

These graphic elements give his paintings the feel of urban signage or coded street language, similar to the marks hobos once left to communicate silently in unfamiliar places.

Symbols of Capitalism

Basquiat frequently used:

- Copyright symbols (©): To mock the commodification of art and Black culture.

- Dollar signs ($): Often scrawled or juxtaposed with words like “profit” or “sucker,” hinting at exploitation.

- Logos and brands: Referencing how identity is bought and sold.

These motifs underscore his deep skepticism toward the art market and capitalist systems. In this way, Basquiat meaning becomes a form of protest against the very world that celebrated—and consumed—him.

Anatomical Drawings

From spinal columns to hearts and brains, Basquiat’s diagrams suggest both clinical detachment and personal vulnerability. These aren’t just body parts—they are metaphors for the systemic violence done to Black bodies through medicine, incarceration, and labor.

They also reflect how Black men, like himself, were often seen in pieces—dissected, judged, reduced—never whole.

Numbers and Scientific Notation

Basquiat often integrated:

- Equations

- Chemical terms

- Scientific charts

These references critique the Western obsession with rationalism and “objectivity.” By pairing scientific codes with symbols of suffering or Black identity, he exposes the cold machinery behind things like eugenics, criminal justice, or colonial rule.

Religious and African Symbols

There are halos, crosses, saints, and spiritual imagery scattered through his work—often combined with African motifs and masks. These reflect a hybrid spirituality, rooted in ancestral memory and Catholic upbringing but altered by the brutal realities of American life.

His Gold Griot piece, for instance, references the West African griot—the oral historian and cultural keeper. The symbol is as much a self-portrait as it is a cultural tribute.

FAQ: Basquiat Meaning

What does “Basquiat” mean in art?

Symbolically, Basquiat means radical creativity, cultural rebellion, and visual poetry. His name is now synonymous with the defiance of traditional artistic and racial boundaries.

What is the meaning of Basquiat’s crown?

The crown symbolized royalty, respect, and elevation. It’s used especially for Black historical and cultural figures who were often overlooked or erased, as well as figures of Basquiat’s own imagination.

Why is Basquiat’s art hard to interpret?

His work often defies literal meaning. He used abstraction, coded language, and cultural references that invite reflection rather than explanation.

What does Basquiat represent today?

Today, Basquiat meaning embodies artistic freedom, racial consciousness, and the blending of high and low culture. He remains a voice for the unheard and unseen.