Back in the mid-1980s, Andy Warhol made a series of digital artworks on an Amiga 1000, a personal computer created by Commodore International. The artist, tapped by the company to be a spokesperson for the computer’s multimedia capabilities, created a few public pieces as part of a marketing campaign, but it was unknown if he had made any digital artworks on his own time.

Decades later, we now know he did. Stashed away on dozens of unlabeled floppy disks was a treasure trove of never-before-seen Warhol works that were slowly deteriorating. A multi-year, collaborative effort between a team of artists, museum professionals and the Carnegie Mellon Computer Club unearthed 28 works of art and a host of 1980s graphics software that Warhol used to create these digital pieces.

It was a huge discovery, and one that might have never been made if it weren’t for the curiosity of Cory Arcangel. A few years back, the NYC artist, a self-proclaimed “Warhol enthusiast,” had watched a clip of Warhol painting a digital portrait of Debbie Harry during an Amiga demonstration.

It got Arcangel thinking: If Warhol had created these public paintings, what were the chances that he made others, too? So the artist took at trip to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Penn., to see what he could find. “It was really just out of curiosity,” he recalls. “We asked, did Andy Warhol have any discs or hard drives?” (He did). In fact, the Warhol museum had heaps of Warhol’s hardware and nearly 40 floppy disks that had never been explored. “No one had ever attempted to see what was on them,” says Arcangel. “It was a complete mystery what they contained.”

Digital Archaeology

There were reasons for this. Because of the disks’ age and fragility, extracting data posed a serious risk. The archiving and viewing process could irreversibly damage the content, but letting the disks slowly degrade was an even worse option.

Arcangel got in touch with Golan Levin, a professor of art at Carnegie Mellon and head of Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry. Levin pointed Arcangel in the direction of the university’sComputer Club, a group of students who just so happened to have experience with retrocomputing. Amigas in particular.

“We had to make sure everyone understood the risk,” says Michael Dille, a former member of the club who worked on the Warhol project. Extracting the content wasn’t just a matter of sticking a disk in a drive and seeing what popped up. “That’s definitely not how it went down,” says Levin of the process.

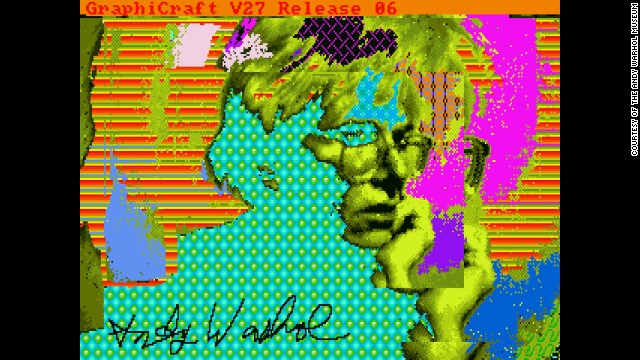

Using a KyroFlux, the Computer Club was able to generate an archival dump of the disks’ data. They found files names like “campbells.pic” and “marilyn1.pic”, a clear and exciting clue that something was on the disks. Issue was, they couldn’t read the unknown file format. The club spent months reverse engineering the GraphiCraft software in order to actually open the files. “It was kind of like a treasure hunt,” says Arcangel.

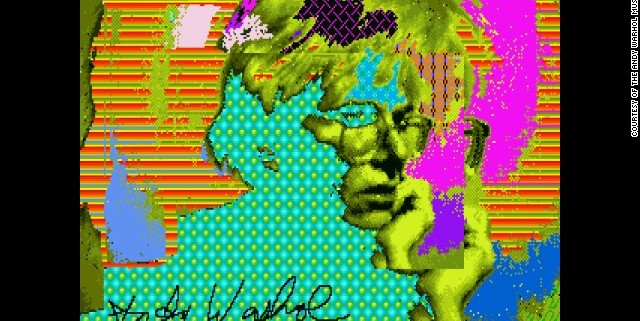

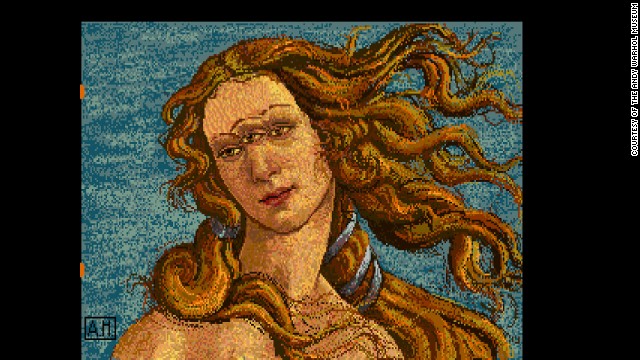

It was worth the work. They found images give fascinating insight into Warhol’s many digital experiments. Pieces like Venus were made using GraphiCraft software’s basic functionalities; the three identical eyes you see were simply a matter of accessing the clip art library. And the digital reproduction of Warhol’s famous Campbells soup cans shows his use of the line tool. Without any tweaking, the original works are inconceivably small—about 300 x 200 pixels—because of the low resolution of the screen.

In the Debby Harry clip, you see Warhol clicking away on the graphic program, using flood fills to color Harry’s blonde locks a shocking shade of yellow. It’s mesmerizing to watch, if only to show how far our digital art tools have come. It’s fun to imagine Warhol and his assistants sitting at his desk, saying “watch this!” as he copy and pastes a Marilyn head. Today these functionalities seem commonplace, primitive even, but back in the ’80s Warhol was really a digital pioneer, one of the first people to explore how tools could be used to make art. “It’s a really early instance of a professional digital art studio,” says Dille. “Perhaps the first.”

BY LIZ STINSON, WIRED

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!