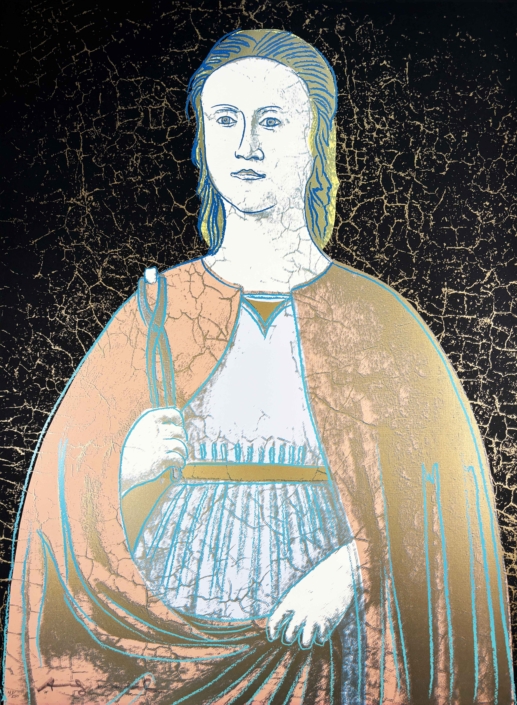

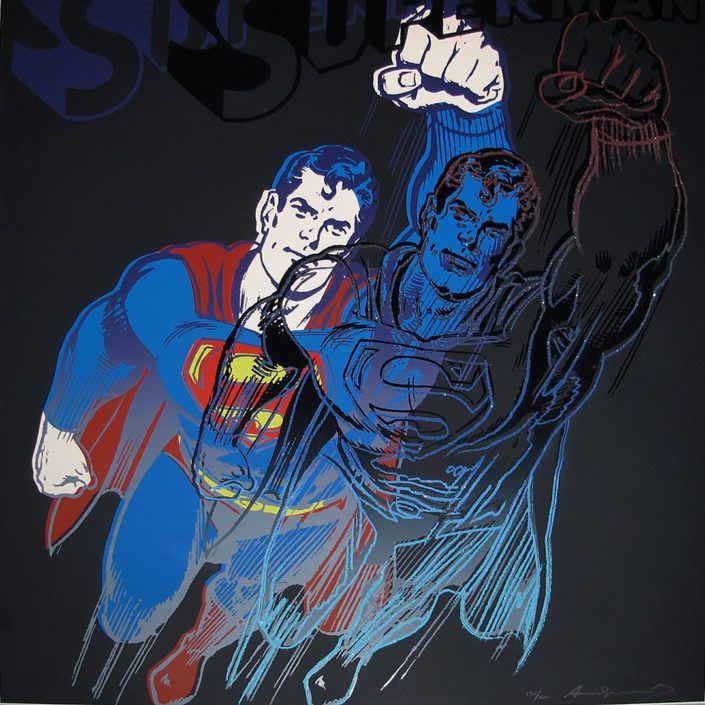

Known for his cultivation of celebrity, Factory studio (a radical social and creative melting pot), and avant-garde films like Chelsea Girls (1966), Warhol was also a mentor to artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. His Pop sensibility is now standard practice, taken up by major contemporary artists Richard Prince, Takashi Murakami, and Jeff Koons, among countless others.

Andy Warhol’s Early Life

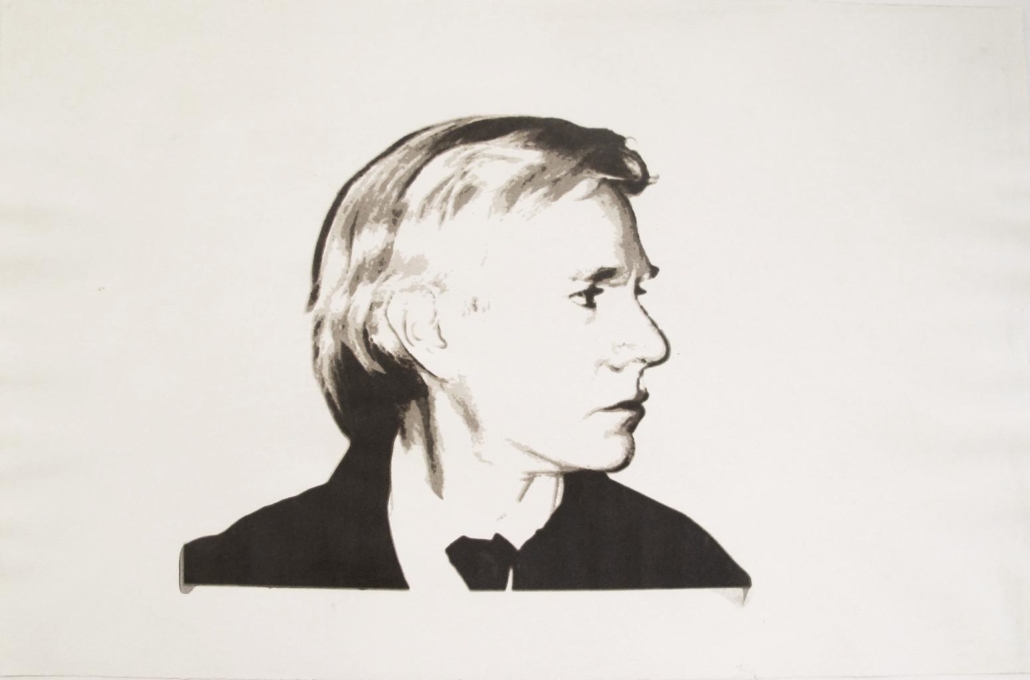

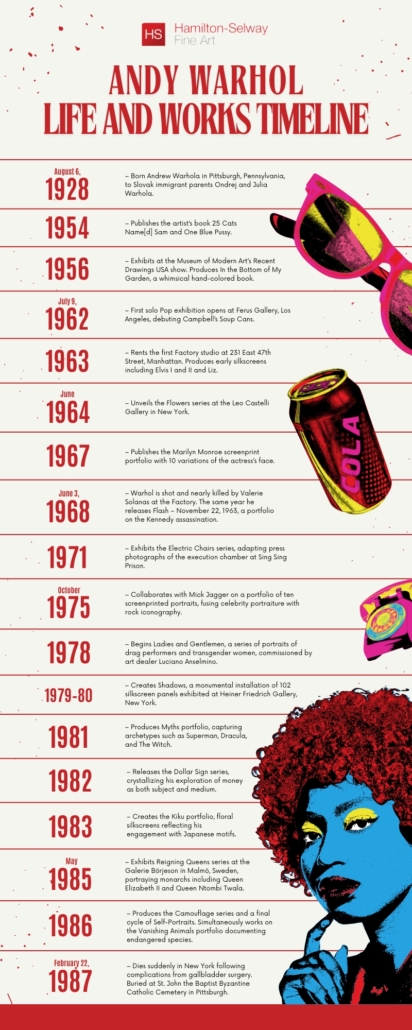

Andy Warhol was born on August 6, 1928, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania as Andrew Warhola. His mother Julia was an embroiderer, and his father Ondrej was a construction worker. Immigrants from Slovakia, the family, clung to their Eastern European heritage, regularly attending Catholic mass and spending their time in the ethnic areas of Pittsburgh.

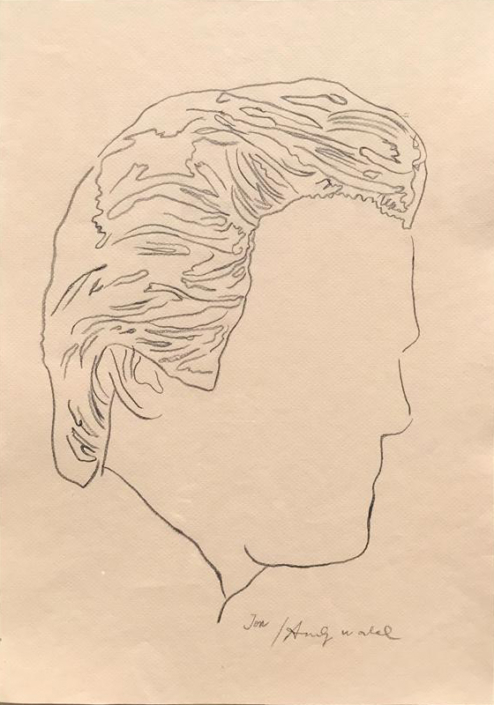

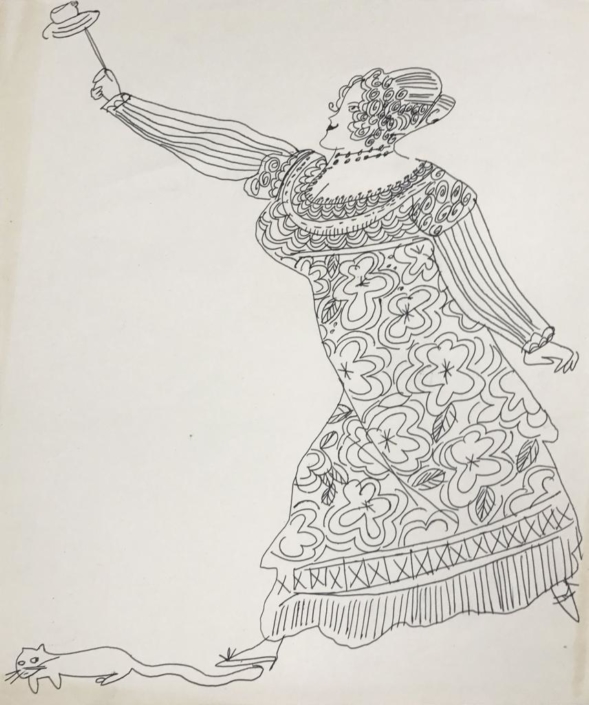

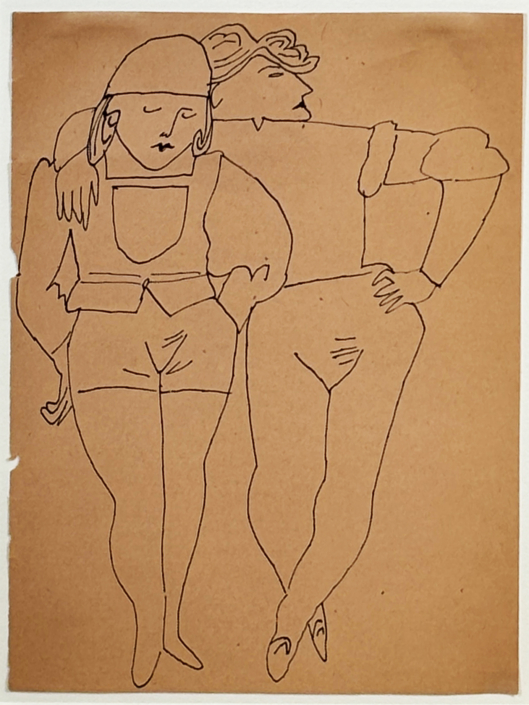

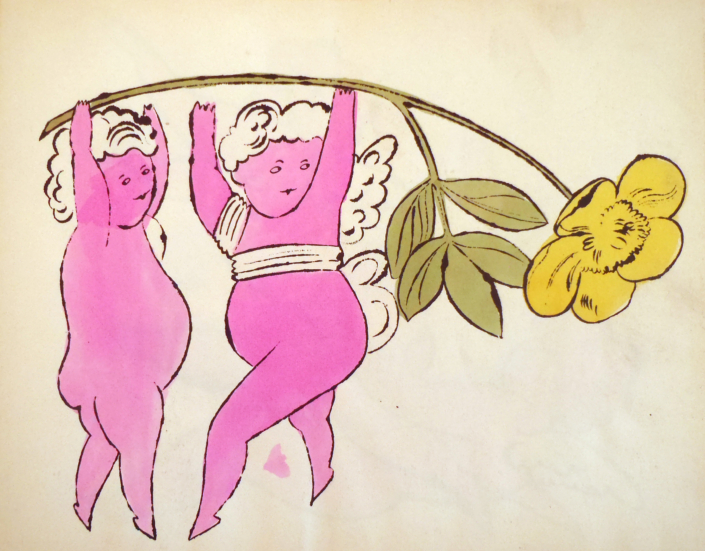

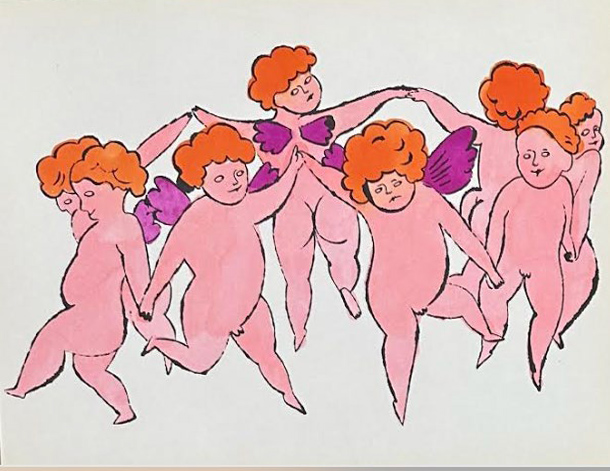

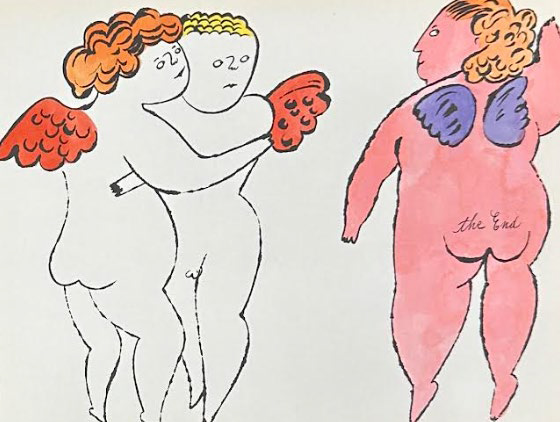

Warhol’s artistic genesis began at the age of 8 when he contracted Sydenham chorea (a rare hereditary nervous disorder) that left him bedridden for several months. As a means to comfort Andy Warhol during this difficult time, his mother took it upon herself to give him drawing lessons. Through these lessons, Warhol grew to appreciate drawing as well as other artistic mediums such as cinema and photography. After his recovery his mother gifted him with a camera and set up a dark room in the family basement, further encouraging his artistic pursuits.

The Artistic Career of Andy Warhol

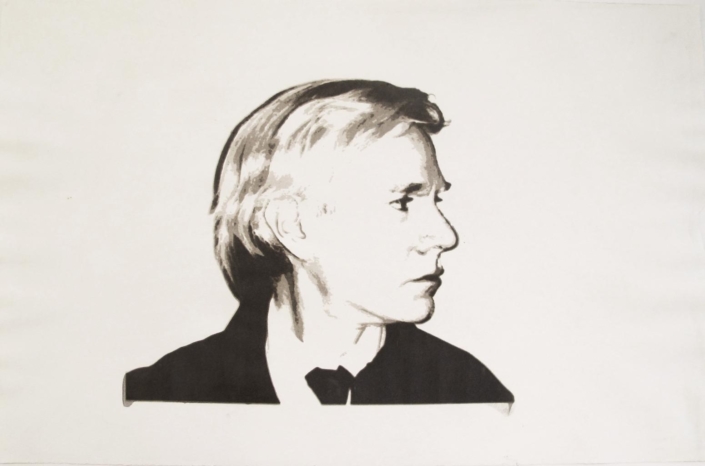

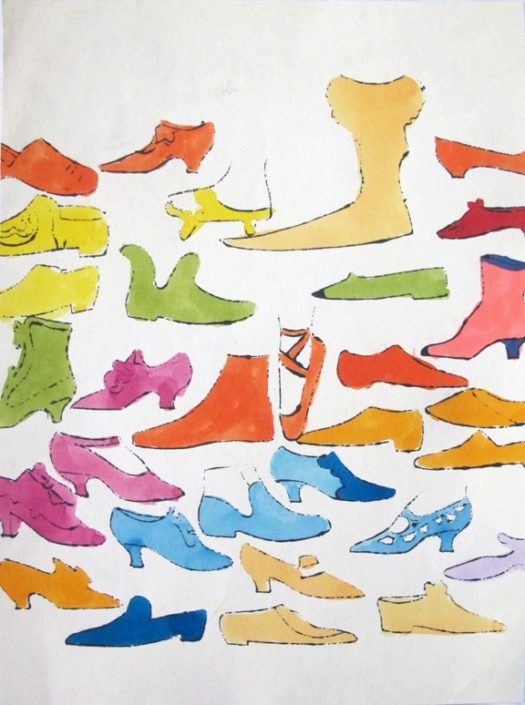

Andy Warhol attended Carnegie Institute of Technology (now known as Carnegie Mellon University) in 1945 and graduated with a BFA in 1949. Shortly after, he moved to New York City, changing his last name and beginning his pursuit towards an artistic career. Warhol eventually started working at Glamour magazine as a commercial artist, paving the way to become well-respected in the world of art. It was during this time where he gained notoriety, winning awards for his unique style and techniques in his artistry.

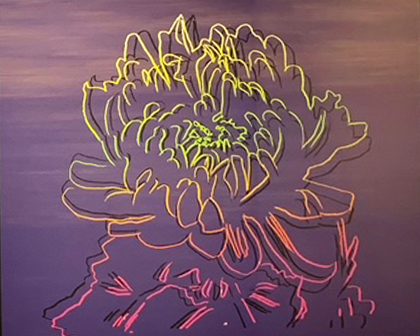

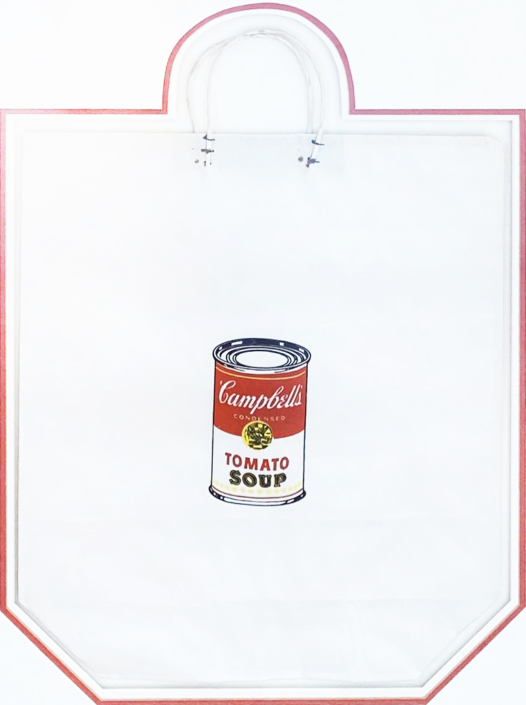

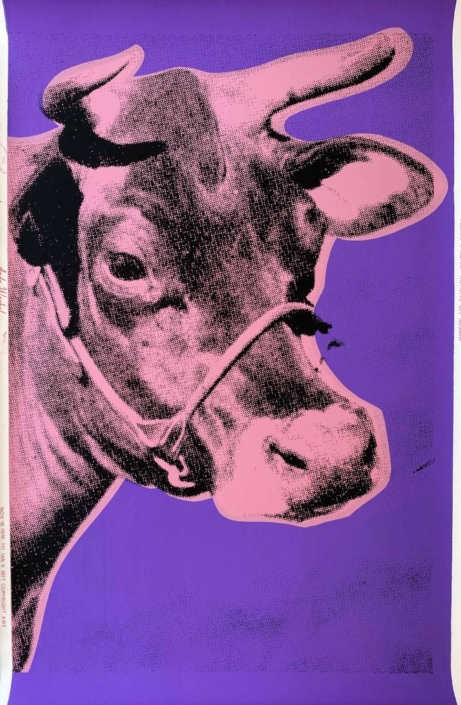

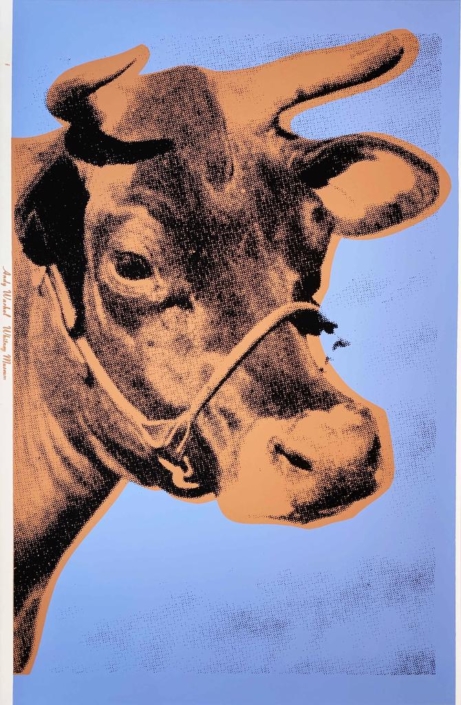

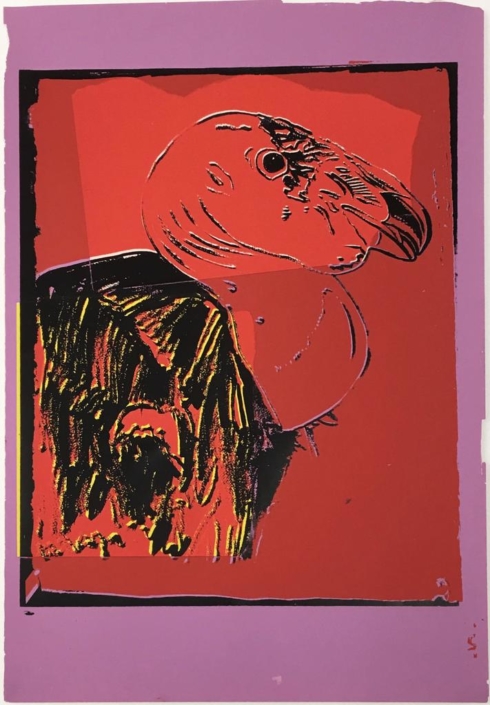

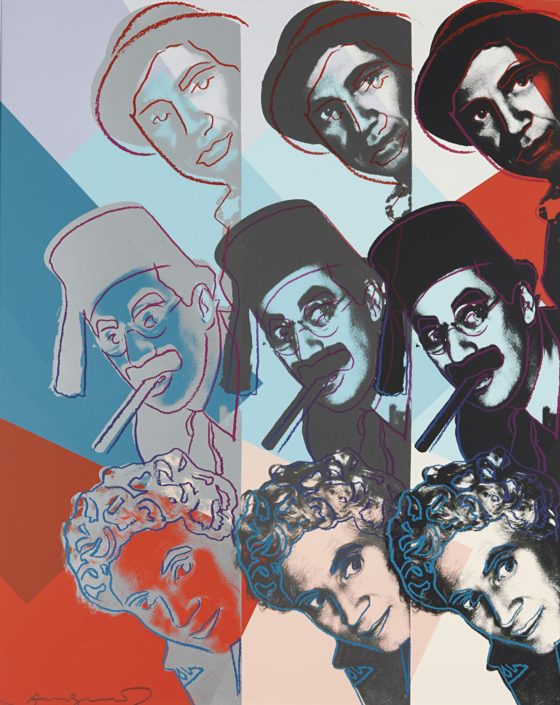

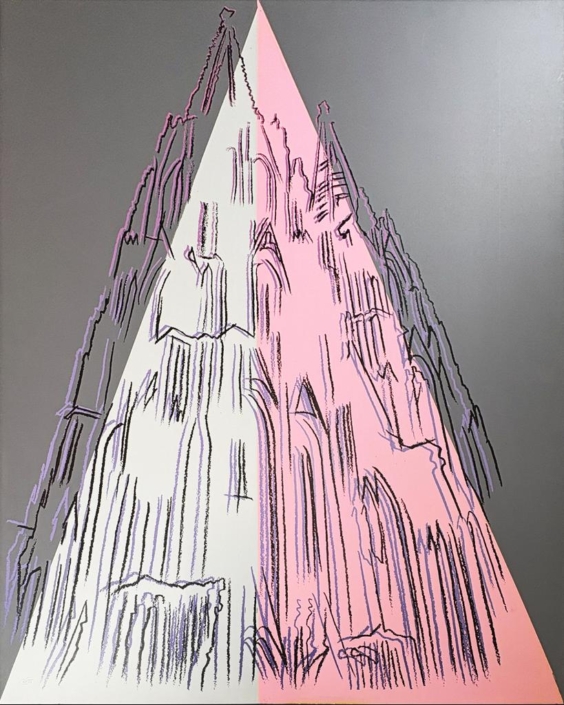

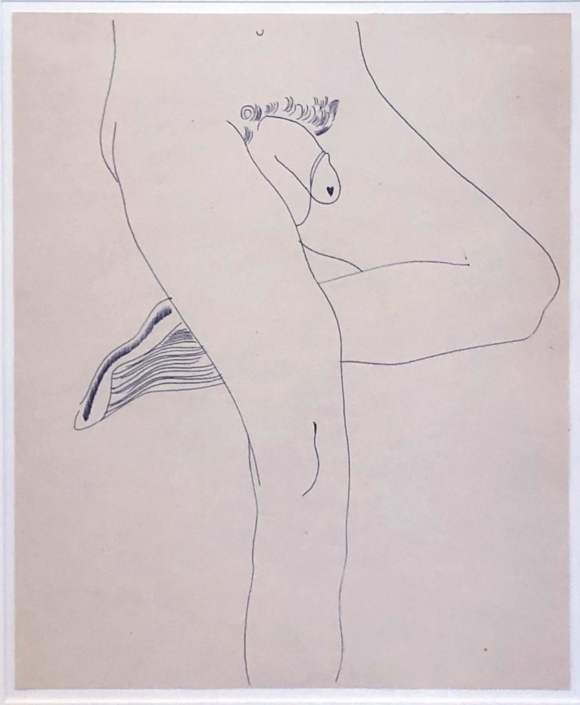

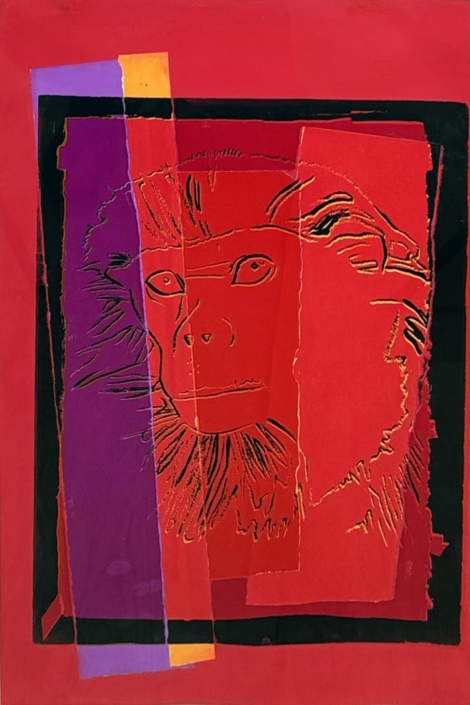

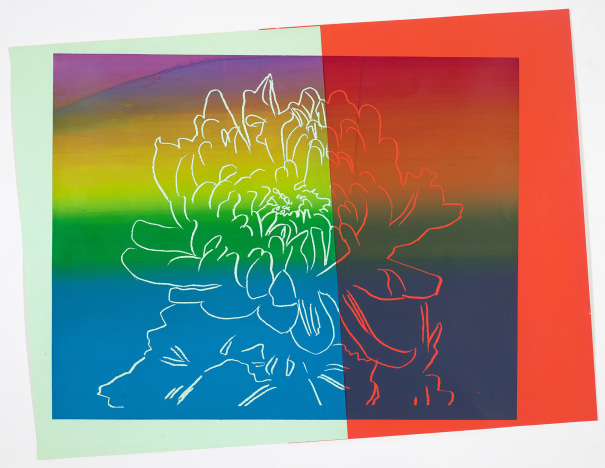

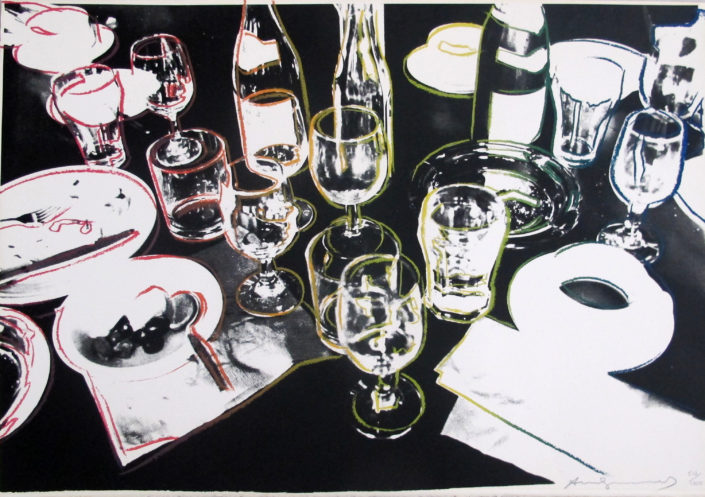

Warhol started transitioning from photography to painting in the 1950s, culminating in arguably his most notable works in the realm of “pop art.” One of the most striking pieces created during this movement was his iconic Campbell’s soup cans in 1962. It was with these types of works that Warhol propelled both himself and his art style into the spotlight. Warhol began exhibiting his art during this time as well at the Hugo Gallery, the Bodley Gallery, and the Ferus Gallery.

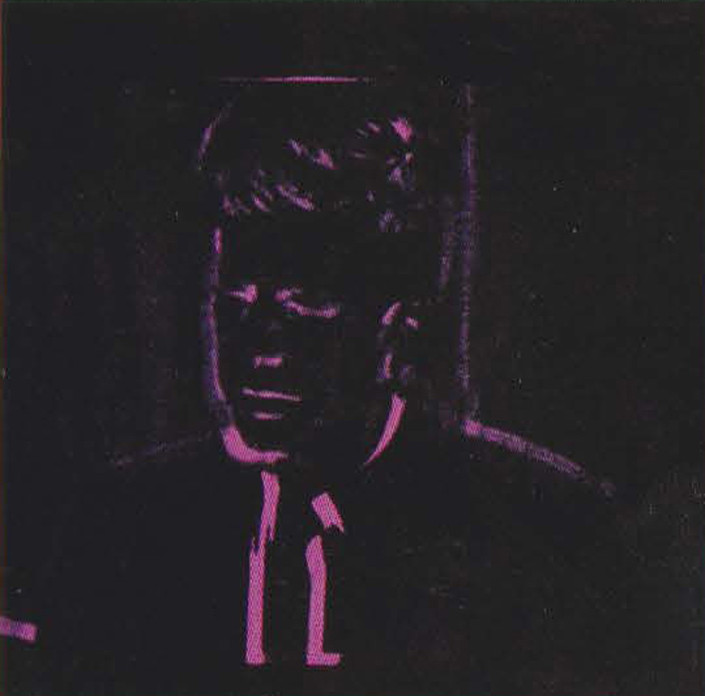

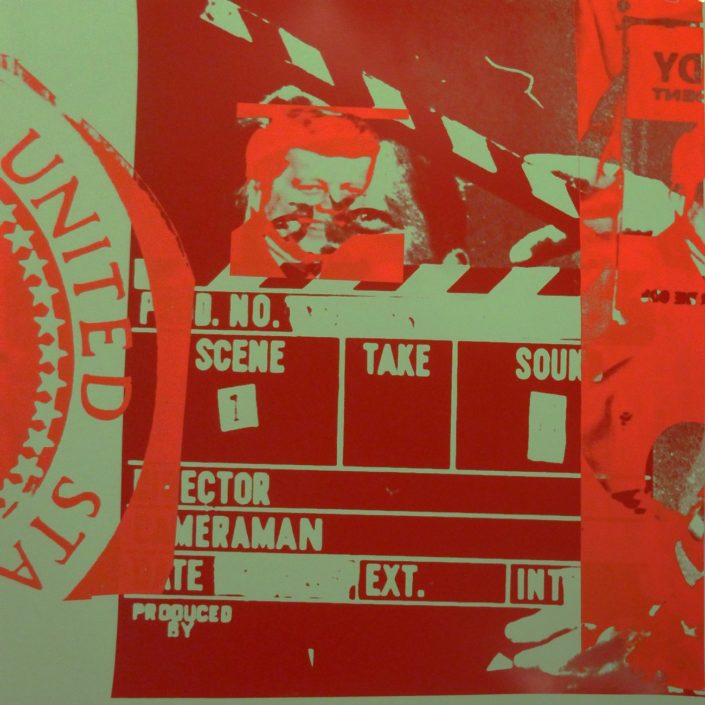

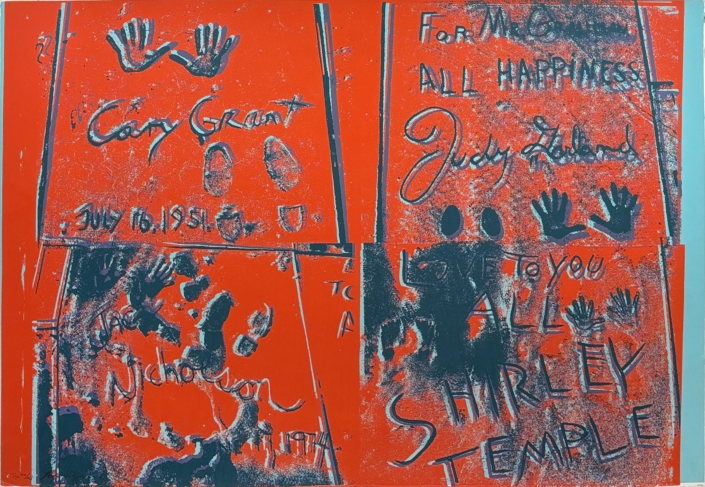

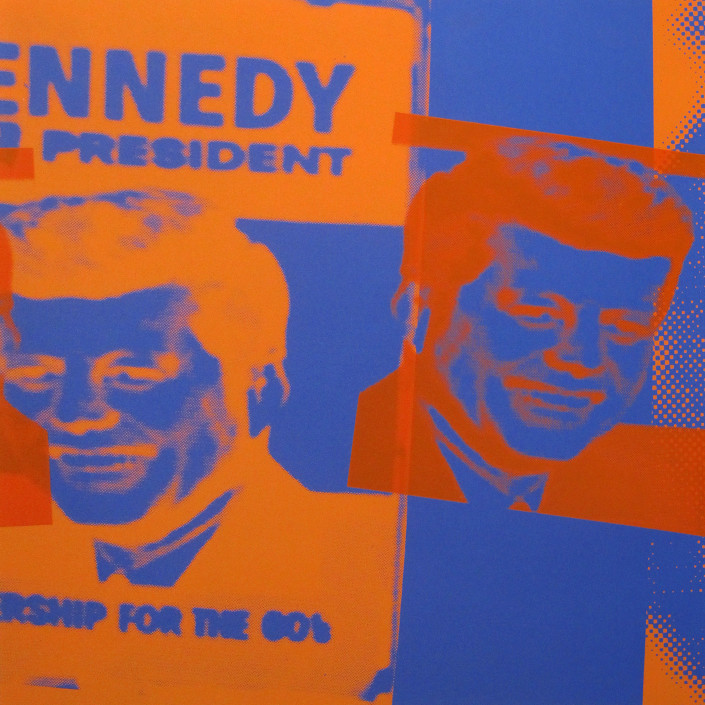

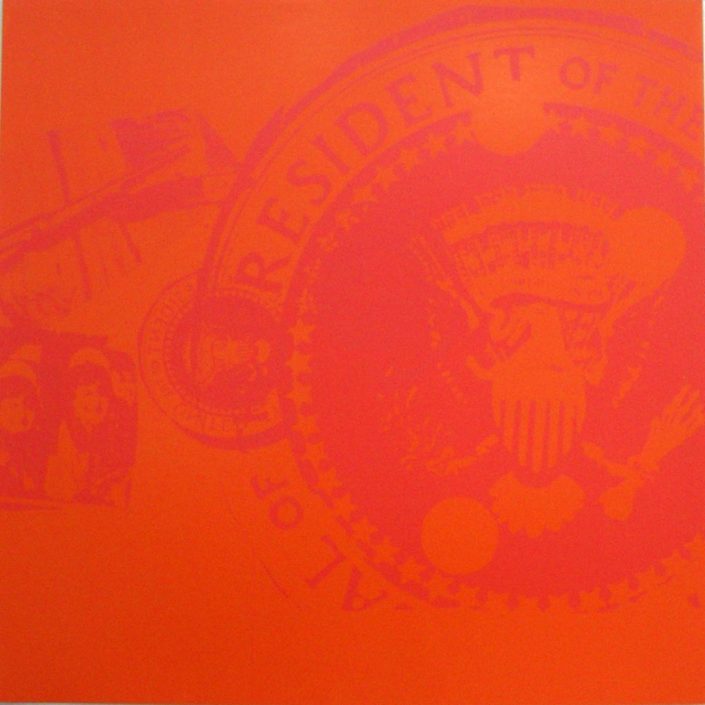

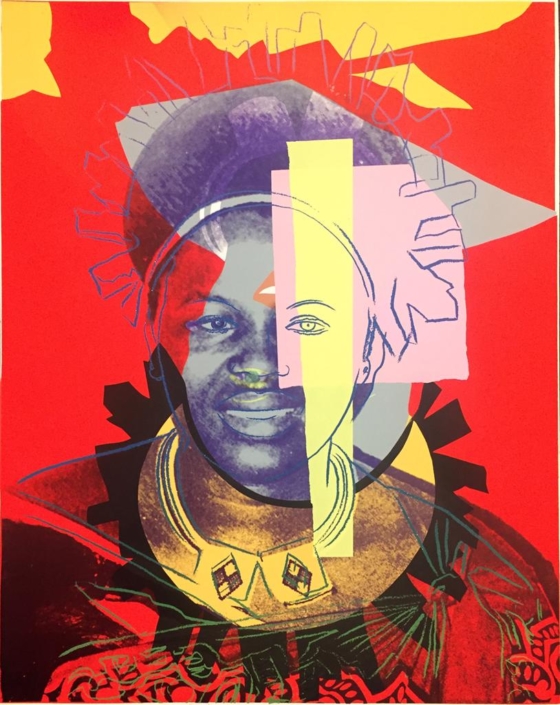

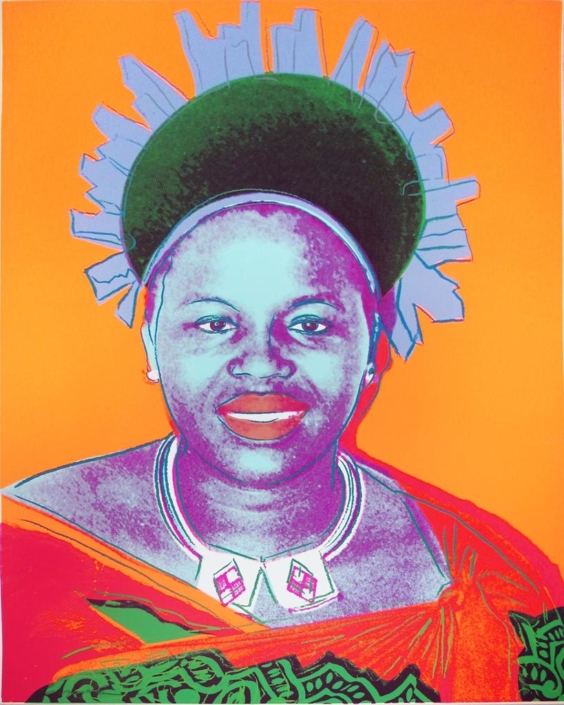

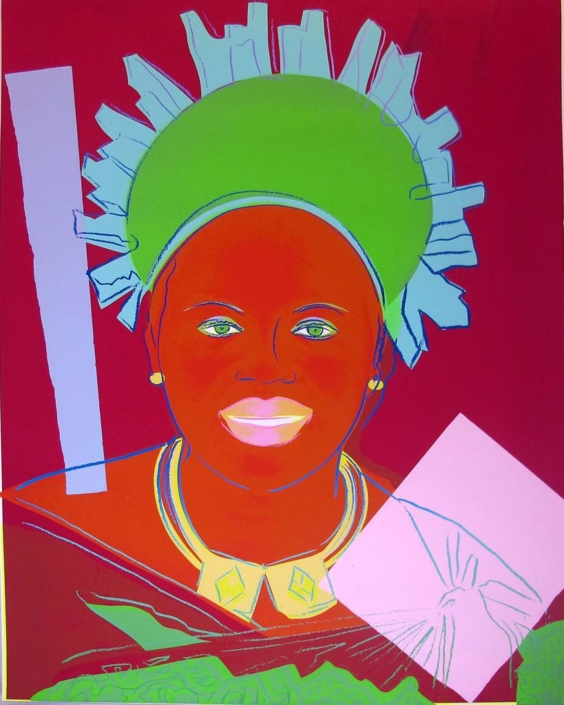

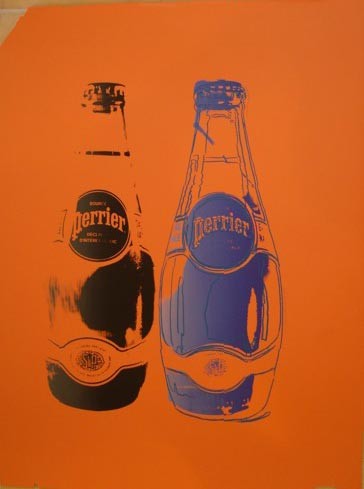

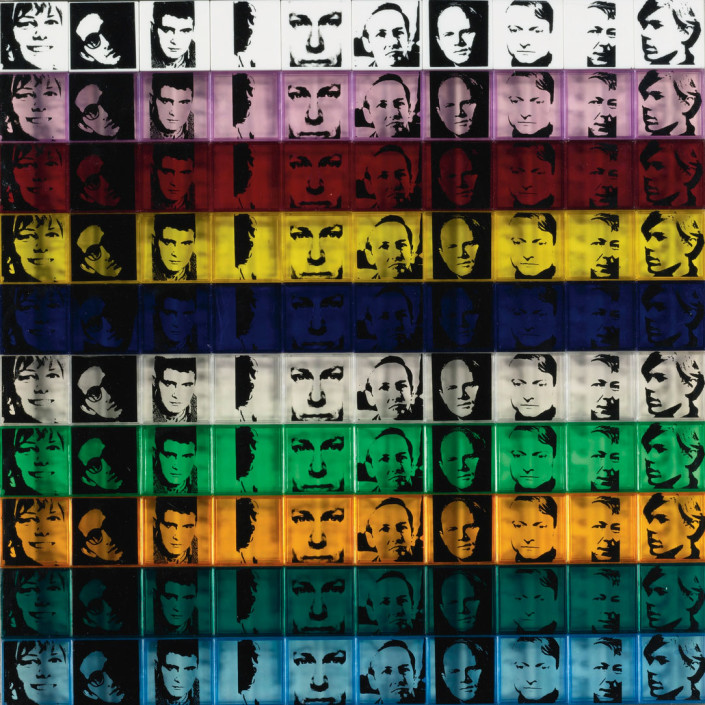

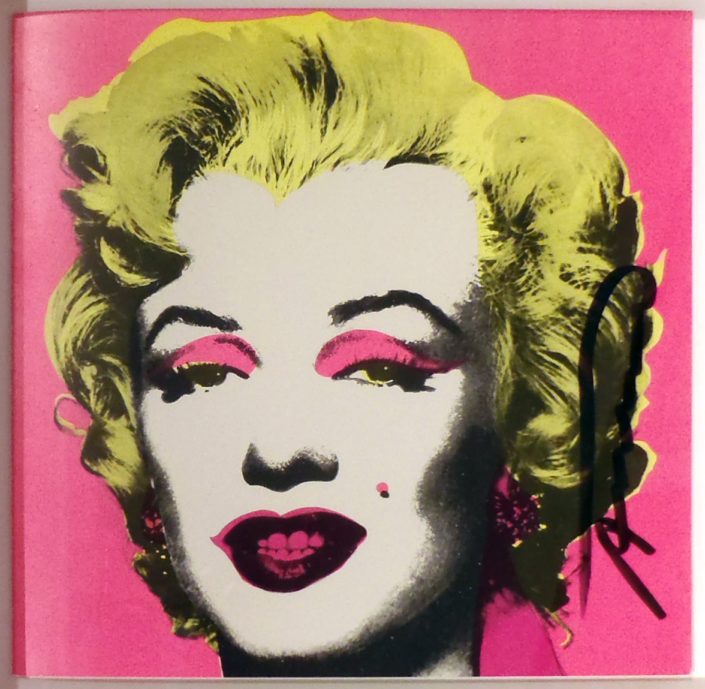

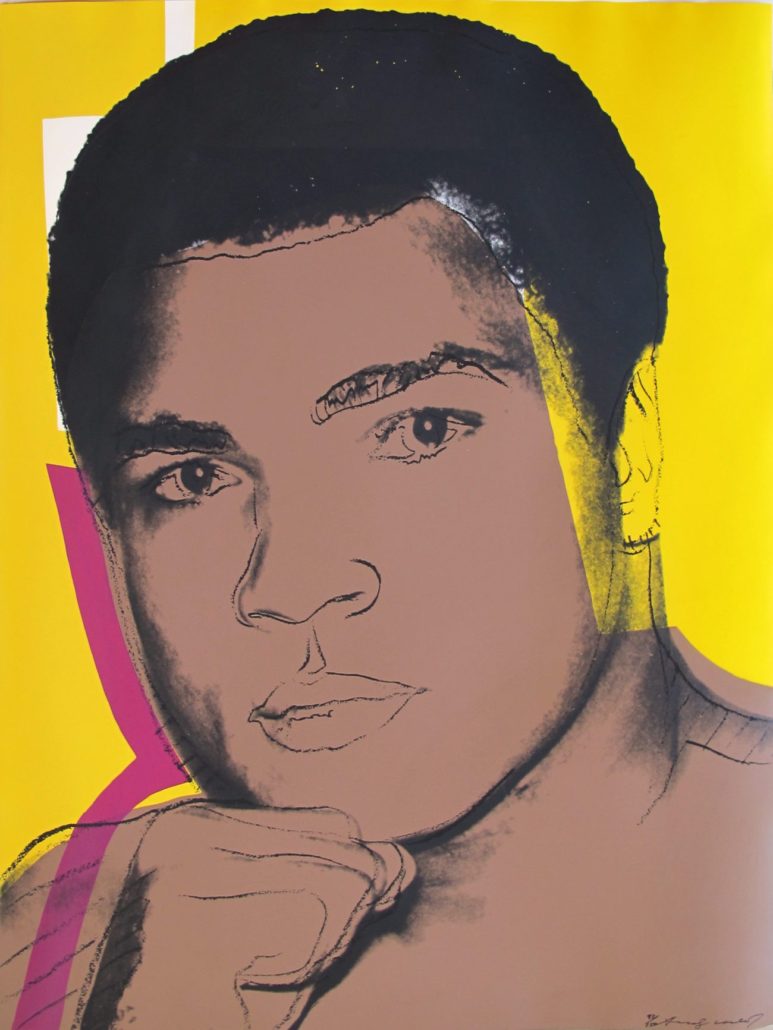

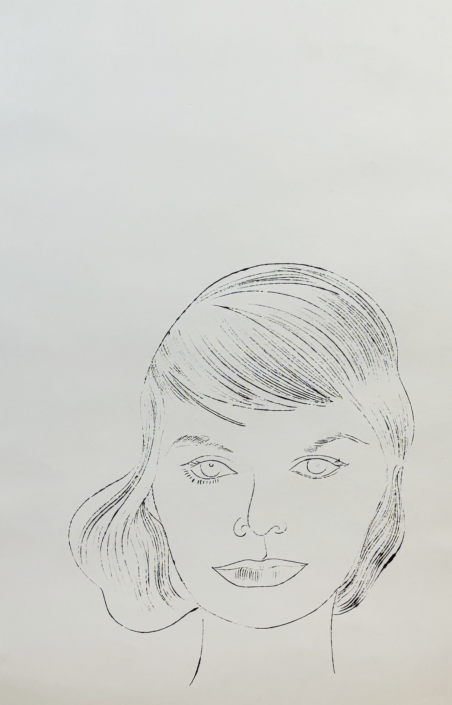

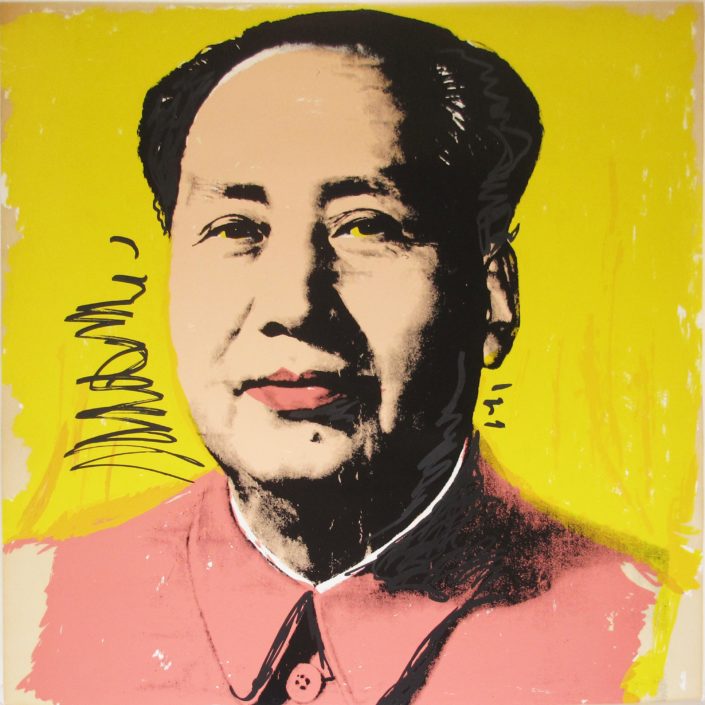

Some of Warhol’s other works during this time included objects such as mushroom clouds and bicycles, as well as well-known people like Marilyn Monroe. In regards to Coke bottles, Andy Warhol had this to say: “What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coca-Cola, Liz Taylor drinks Coca-Cola, and just think, you can drink Coca-Cola, too. A Coke is a Coke, and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same, and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.” As Warhol became more and more famous, he started receiving more and more requests for commissions. It goes without saying that Warhol produced some of his most notable works during this time. In 2008 his piece “Eight Elvises” was sold for $100 million, one of the most valuable Warhol pieces ever sold.

Warhol eventually made arguably one of his most distinct artistic moves in 1964, opening his art studio known as “The Factory.” This studio became an artistic mecca of sorts in New York City. Extravagant parties were frequently held, and The Factory was regularly visited by celebrities of all sorts including the likes of Liza Minnelli and Betsey Johnson. Many of these Warhol “Superstars” drew artistic inspiration from their time at The Factory. While some people shied away from their celebrity status, Warhol did not. Even outside The Factory, Warhol was recognized everywhere he went, particularly at the famous NYC nightclubs like Studio 54 and Max’s Kansas City.

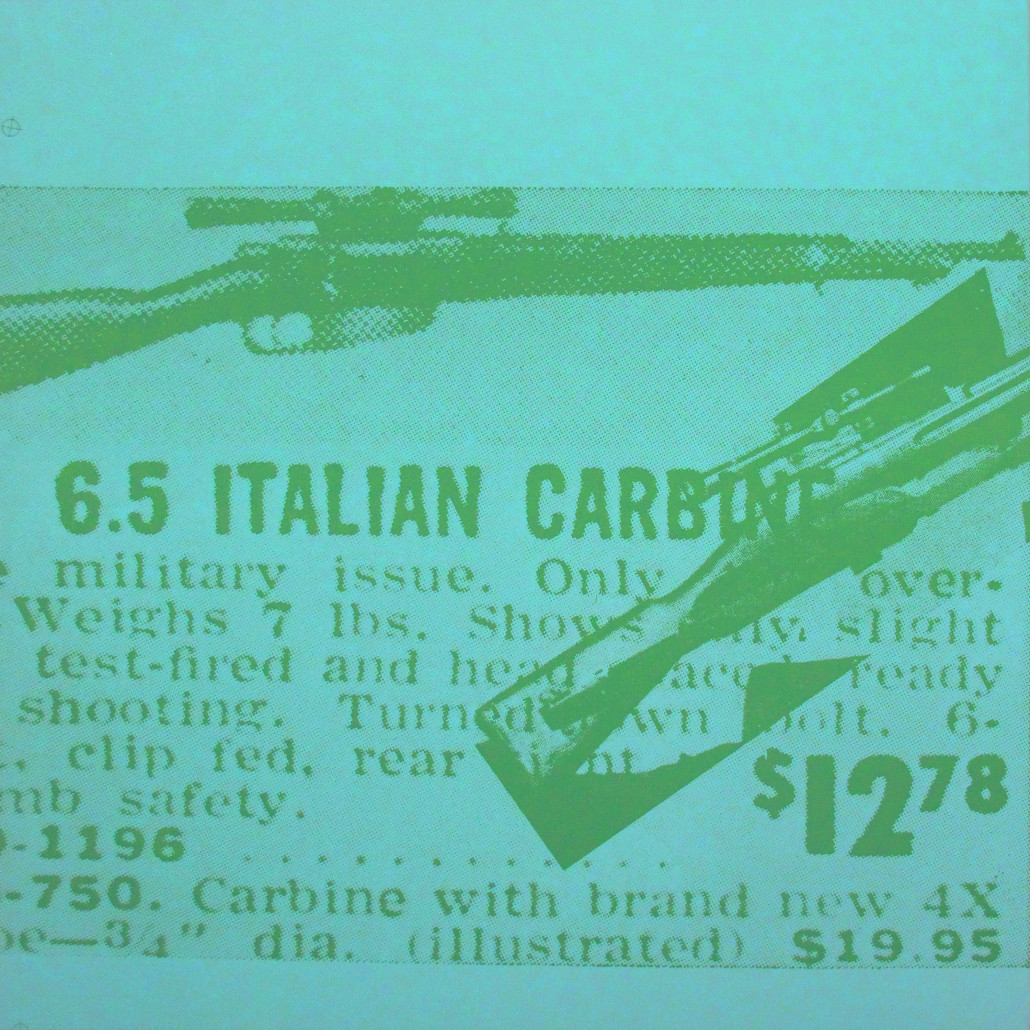

Despite his popularity, Warhol wasn’t liked by everyone. In June of 1968, his life nearly came to an abrupt end, with Radical Feminist writer Valerie Solanas entering his studio and shooting him and Mario Amaya, an art critic, and curator. An incident with a script Solanas had presented to Warhol disgruntled her. Soon after the shooting, Solanas was arrested and plead guilty in court. Though Amaya recovered quite quickly, Warhol was severely wounded and had to spend several weeks in the hospital. For the rest of his life, Warhol had to wear a surgical corset.

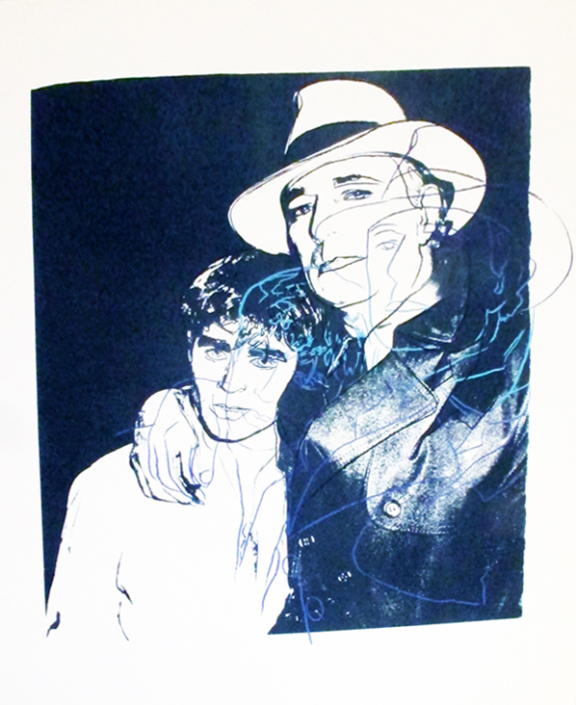

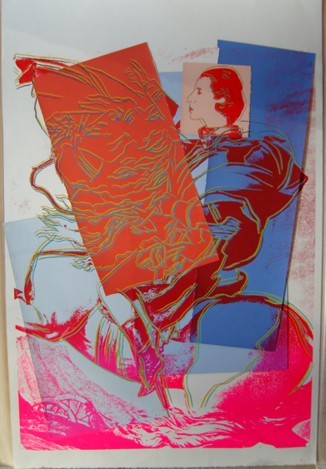

The 1970s were a quiet time of artistic exploration for Andy Warhol. During this time he published his loose autobiography The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again). While he did continue to build his portfolio of celebrities to use in his art, like Mick Jagger and Diana Ross, Warhol opted to be more of an observer at social gatherings, quiet and contemplative.

Andy Warhol’s Death and Legacy

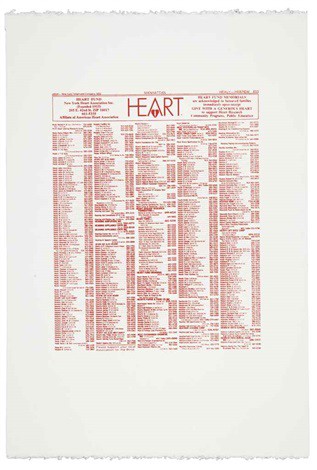

Towards the end of his life, Warhol suffered from gallbladder problems, forcing him to go back under the knife at New York Hospital on February 20, 1987. While the operation seemed successful and his recovery apparent, heart complications led to his death two days later, at the age of 58. His body was returned to Pittsburgh for an open-coffin wake. After the ceremony, he was lowered into the grave, with an Interview magazine, an Interview T-shirt, and a bottle of the Estee Lauder perfume “Beautiful.” Warhol was buried next to his mother and father at St. John the Baptist Byzantine Catholic Cemetery. A memorial service commemorating Andy Warhol was held on April 1, 1987, in New York City.

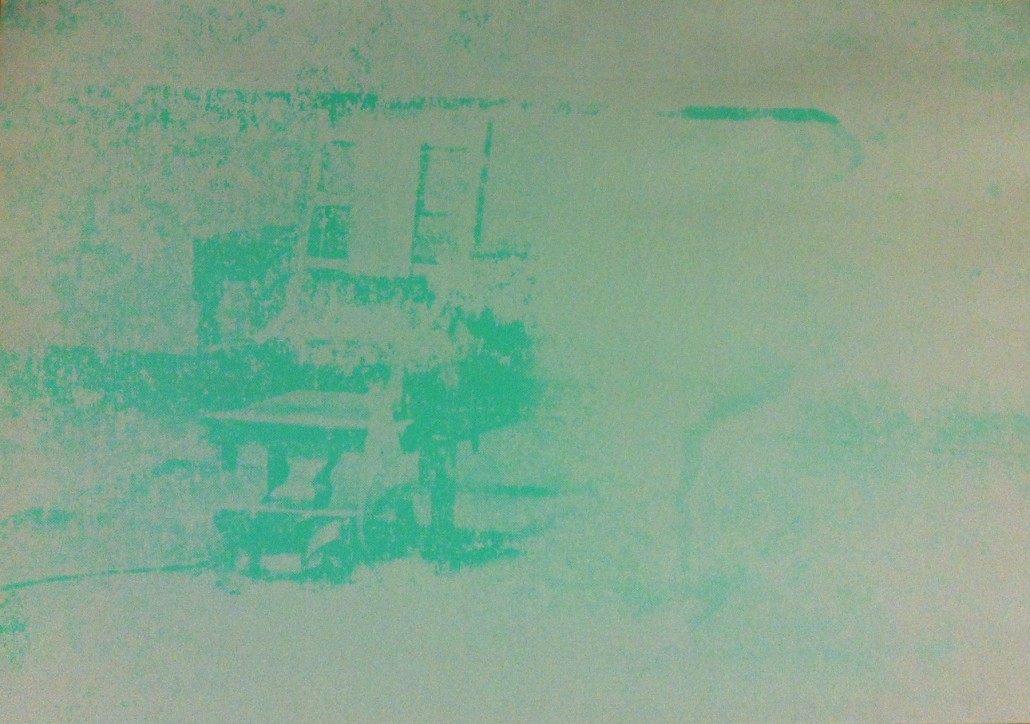

Warhol’s life and work are described as satirizing and celebrating both materiality and celebrity. His distorted art based on brands and personalities might be analyzed as a critique or judgment of a culture that placed so much importance on money, fame, and appearances. However, one could say that Warhol’s obsession with these same brands and icons translates to a respect and celebration of these very ideals. Perhaps there is a little of both aspects.

Warhol’s will dictated that most of his estate would be used to create a foundation for the advancement of the visual arts. The proceeding auction grossed more than $20 million. These funds were used to create the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. To this day, the foundation serves as both the estate of Andy Warhol and a place to “foster innovative artistic expression.” The Andy Warhol Foundation makes generous grants to various non-profit arts organizations and has hosted several programs to promote this mission. As for Warhol’s art, many of his works and possessions are on display at The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. The foundation donated more than 3,000 works of art to the museum.

Read Less

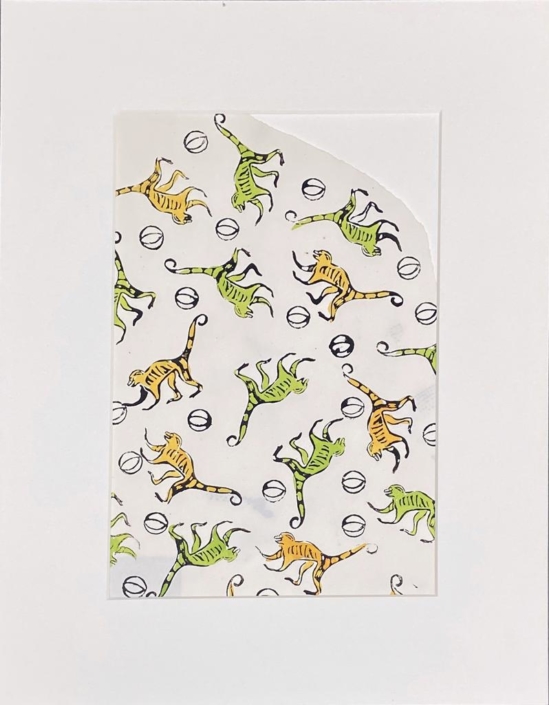

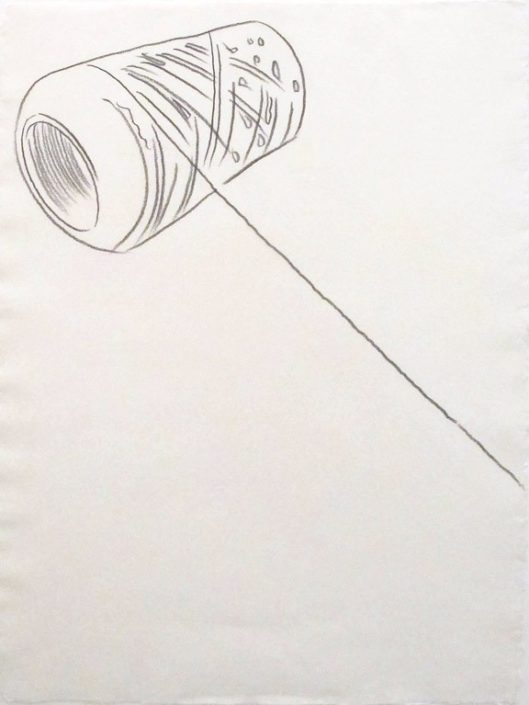

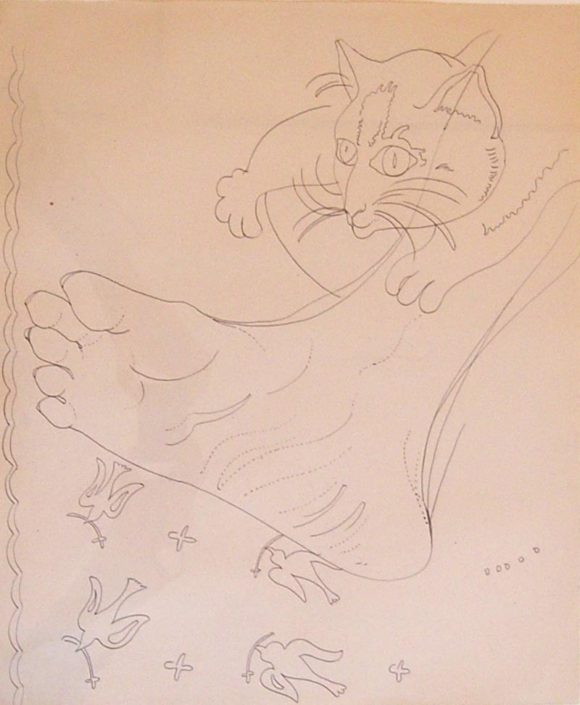

![Andy Warhol | 25 Cats Name[d] Sam and One Blue Pussy IV.57B | 1954 Andy Warhol | 25 Cats Name[d] Sam and One Blue Pussy IV.57B | 1954](https://hamiltonselway.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/25-Cats-IV.57B-12_190-HR-460x705.jpg)

![Andy Warhol | 25 Cats Name[d] Sam and One Blue Pussy IV.56B | 1954 Andy Warhol | 25 Cats Name[d] Sam and One Blue Pussy IV.56B | 1954](https://hamiltonselway.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/25-Cats-IV.56B-12_190-HR-460x705.jpg)

![Andy Warhol | 25 Cats Name[d] Sam and One Blue Pussy IV.53B | 1954 Andy Warhol | 25 Cats Name[d] Sam and One Blue Pussy IV.53B | 1954](https://hamiltonselway.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/25-Cats-IV.53B_12_190_HR-460x705.jpg)